Large cow herd and animal health collide

In terms of animal health, to manage a company with 400 cows demands much more effort than a sole proprietorship. Some of the growing farms have a grip on this, and some don’t.

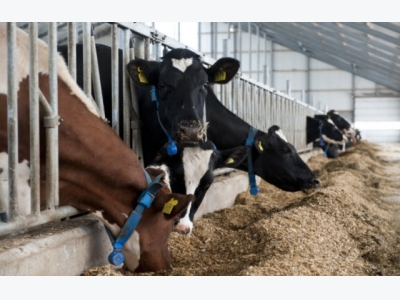

Large cow herd and animal health collideA large company can be more efficient and more economical. But a farmer should put in more effort per animal to maintain a healthy herd. Photo: Wick Natzijl

Ynte Schukken, director of animal health at the Dutch animal health service (GD) knows what he is talking about. In the US, he has gained experience with large companies and animal health. “Dutch farmers who settled in Ohio with a new big business, had it go wrong in some cases.

They took the leap from a one-man business to a company with nearly 700 cows and staff all at once. Half could manage it well. The other half ran into big disappointment and failure. They tried what I call ‘staying animal-farmer’, remaining the way they were in the Netherlands with their business of 60 to 100 cows. That’s not possible. You can’t spend all your time on your animals. That’s a sure way to get in over your head. You lose grip of what’s important. You need to manage and control staff. Therein lies the key to success.”

What lessons can be learned from the Ohio farmers?

“It’s a rigorous step going from a sole proprietorship to a company with 700 cows and not made so quickly in the Netherlands. Growth is gradual. This means you can get used to it, but it’s a big misconception that if you can create a smaller herd, then you can go for a big one. That’s not how it works. Growing into a large herd and management is not for everyone. That requires different abilities. Once you start working with staff, management plays an important role. A good manager ensures that the work is done properly, even if he is not there himself. You have to enjoy letting others do the work. You should view employees on a larger scale, your brother’s son is staff too and if you do business as a team of two or three brothers together, it is important that you know exactly what each of you are doing and that you make clear agreements. Do not assume that others will just know about everything you do.”

Is that a warning for growers?

“You don’t automatically move from farmer to manager. Companies that have grown strongly in recent years will notice that. Some will decide not to grow or even switch back to smaller companies, because they do not have it in them to manage, or are simply not enjoying themselves. They may be fine farmers, but the size is not right for them. It is important to choose an alternative that you feel good about. For one person that’s switching to organic, to a different niche or perhaps using a robot instead of staff or adding a different branch.”

Downshifting, how many companies are involved?

“I do not have exact figures. I estimate half.”

For others: Growth continues unabated?

“Growth is attractive. A large company is more efficient and more economical. You can use housing and cheaper machines, the quality of the food goes up, often it’s better for animal welfare, environmental engineering is well regulated, innovation is easier and also socially attractive because you can work with staff in a team. Rationally speaking, that is a good development that continues worldwide. With respect to animal diseases and infection ‘economy of scale’ is irrelevant. The exact opposite is the case in animal health. You should do a lot more and put in much greater effort per animal to have a healthy herd and keep it that way. “

What makes large companies vulnerable when it comes to animal health?

“Two reasons. The first is that large companies have a higher potential for disease-introduction. It’s harder to keep infectious diseases like Salmonella and para tuberculosis out. There is more animal traffic. As an entrepreneur you have to keep an eye on your ‘biosecurity’ twice as well. Watch what you buy, where they come from and what the health status is, but also beware of introduction from the wild, guests or other things entering the farm. Does the company you buy animals from take part in health programmes? Is the status equal to your own status? The second reason is that a disease maintains itself more easily in large companies; extinction of infection is less likely. At large companies, there is a continuous inflow of heifers in the dairy herd. Often heifers are still sensitive because they have not been previously infected, and can more easily maintain an infectious disease in the herd. Large also means that an infection spreads easily, since there are more contacts per animal. Compare it with the children in a family or in a large nursery. If one has a cold, the whole nursery gets the cold. In short, a large company should really be on top of and pay close attention to preventive health.”

Dotting the ‘i’ - How?

“Make sure you have a good and close relationship with the vet. Run through health programmes. Plan out how to tackle your problems. And work with rigid protocols for staff. You cannot count on your staff being all-knowing. I was recently at a company with eight milkers. One dipped, the second sprayed, and the third did nothing at all. Make things clear! Be very careful about writing down how things should happen, and train your staff on that. Motivate them as much as possible.”

Working with protocols is the main key. Does that happen enough?

“Nowhere near everywhere. The step from going from farmer on one-man business to being a larger company manager has not yet been made for them. There are entrepreneurs thinking about it. We’re in the middle of that process.”

Where can I, as a farmer, come into the possession of the knowledge that goes into making a good protocol?

“Write it out yourself first, as you think that the work should be done. And then test it. That may work fine with a veterinarian, but also with a consultant, or a spokesperson. Please realise that every business is different and therefore also requires company-specific protocols.”

Does that vet know exactly how things go?

“GD will give vets special courses, how to deal with animal health using protocols, how to make protocols and how to work with them. At agricultural schools, they should do so as well. Animal Health for large quantities of livestock is an important part of the veterinary practice. In America you can see that there is a split in veterinary clinics or within a practice. One specialises in animal health from day to day, the other more in the health of the company: risks to image, setting realistic goals, analysing what’s going on, making a plan and monitoring. In the pig and poultry farming such a split is already common, but this is not yet the case in the dairy sector.”

Diseases in big companies don’t run their course quickly?

“This has everything to do with the size of the company. For 400 cows, the risk that the disease will end itself is much smaller than for a company of 50. For example with Salmonella Dublin there is a small chance, say 1%, that an infected animal is a carrier. With 50 cows the chance that one Salmonella bearer is ‘accidentally’ discharged is considerably larger than that in a company of 400 animals where all carriers ‘happened’ to be removed. With accidental discharges, I mean discharge because of, for example, fertility or mastitis. A smaller herd means it’s easier to get rid of a disease than it would be were your herd much larger.”

I can’t get rid of the disease. Is that a signal that the farmer doesn’t have a good grip on animal health care?

“Then you have a problem. Make sure you take care of it, otherwise you’ll have a bigger problem.”

Can proper management of animal health also be monetised?

“A lot of money could be involved in dealing with a disease. In America it can be the case that the bank (financer) of a farm demands to solve a problem with mycoplasma bovis in the herd, otherwise the bank pulls the plug. There are more cases where things are all or nothing. All the more reason to put more effort in managing animal health.”

Ynte Hein Schukken

Ynte Hein Schukken (55) has been the director of Animal Health at the Animal Health Service (GD) in Deventer since August 2001. Before that, he worked as a professor at Cornell University in upstate New York for several years, and at the same time worked as the director of a subsidiary of Cornell’s Quality Milk Production Services. Ynte Schukken is the son of a veterinarian from Heerenveen and graduated in 1987 from the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Utrecht. He has become an expert in the field of epidemiological research into, among other things, udder health. Since mid last year Ynte is also a professor at Wageningen University and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Utrecht.

Có thể bạn quan tâm

Increased gain in calves provides higher milk yield

Increased gain in calves provides higher milk yield The important thing is to decide what is best for the calves when it comes to milk feeding.

Identify and fix your mycotoxin contaminated silage

Identify and fix your mycotoxin contaminated silage Given the uneven distribution of fungi and the mycotoxins they produce in a single lot, proper sampling is key to correctly assessing the specific on-farm

Mastitis prevention with mammary probiotics

Mastitis prevention with mammary probiotics New research shows that the cow’s own lactic acid bacteria, isolated from the bacteria in the mammary gland, could serve as a tool to prevent and treat mastitis