Biological farming ensures dairy farms success

For 15 years, the Muller family, near George, has been using biological farming methods and no-till practices. Their pasture-reared dairy herd is thriving and can be directly traced to the operation’s original 17 cows.

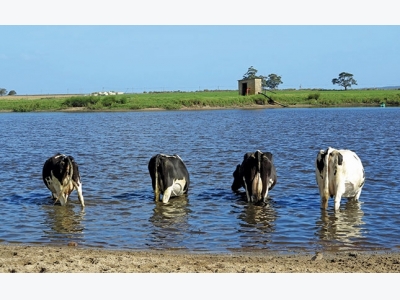

Water is becoming a scarce resource in the Western Cape. Milkwood Dairy uses both surface water and irrigation for the herd and pastures.Photo: Jay Ferreira

The Muller family has been farming on Milkwood farm near George for 33 years. Today, Phil and Georgie Muller run Milkwood Dairy in partnership with Phil’s father, John, who started milking 17 cows on his farm outside Kokstad in KwaZulu-Natal in 1957.

“In 1984, we relocated to Milkwood farm with our cattle,” says Phil, who has been farming in a 50:50 partnership with his father for the past 20 years.

John looks after the finances and cattle records and carries out repairs on the farm, while Phil runs the dairy, pastures and stock.

Georgie, his wife, who consults for Waikato Milking Systems in New Zealand on the software of the company’s milking systems, assists with the running of the milking parlour and feeding system.

A year ago, the Mullers installed an Afimilk computerised milking system, which has helped to increase cow efficiency on the farm.

Farming, not fighting, with nature

“Being conservation conscious and wanting to be sustainable, we’re passionate about biological farming systems,” says Phil.

“We strive to work with nature and not against it. John has always conserved the soil, and

in the past 15 years we’ve had access to minimum tillage seed drills to plant. So we’ve completely stopped disking in an attempt to improve our soils, while at the same time balancing soil minerals and feeding soil life.”

According to Phil, the aim is to build up the organic matter in the soil and limit the use of chemical fertilisers, while maximising the use of cattle manure, as well as chicken manure that is bought in.

“This has all helped us to follow more biological farming methods,” he says.

Automatic weighing to check ration mix

There are 270 cows in milk, 220 heifers and 40 dry cows on Milkwood farm at present.

The Mullers run a pasture-based system, according to which each cow forages about 13kg of pasture/ day and receives 6kg of custom-mixed dairy meal, made up of about two-thirds maize and one-third wheat bran, along with a mineral premix.

As each cow leaves the milking parlour, she walks across a scale that records her weight to ensure that the rations received are correctly constituted.

Phil explains that the cows do not have numbers but names. The original 17 cows’ names each started with a different letter of the alphabet, and all the offspring of a particular cow are given names beginning with the same letter.

He finds it far simpler to remember individual cows by name than by numbers, and this system makes it easy to trace bloodlines as well.

Pastures and irrigation

Milkwood farm extends over 180ha, of which 90ha are irrigated. Phil stresses that when using no-till principles, it is important to ensure the soil is always covered.

Half the irrigated pasture comprises kikuyu-based forage, while the other half is lucerne-based. Italian ryegrass and clover are drilled into the kikuyu pasture during autumn to reinforce and improve the pasture quality for good milk production through the winter months.

Westerwold ryegrass is drilled into the lucerne pastures in early autumn to ensure that there is enough feed for cattle through the winter season.

The Westerwold ryegrass goes to seed in October and the lucerne sprouts again when the temperature starts to increase.

The farm receives year-round rainfall with an annual average of 720mm. But to achieve the required quality and production of milk, the pastures are given an additional 500mm of irrigation water.

“On the dryland pastures, we strive to get the best possible production from the annual rainfall. However, this is highly dependent on the type of season we’re having and the ability of the soil to hold water,” says Phil.

Achieving optimal milk production from pasture has been a learning curve. “Quite simply, good pasture gives good production, and irrigated pasture is the strength of the system, although everything starts with good soil quality.”

While Phil is keen to increase the herd size, he wants to farm sustainably and limit buying-in roughage. Realistically, therefore, the farm is almost at capacity.

“This is mostly [as a result of available] water resources,” he explains. “The Western Cape is getting hotter and drier, and water is a limited resource, so we can’t increase the irrigated area [at present].”

Pastures are irrigated with surface water – runoff from dams and the Moeras River in the Outeniqua Mountains.

Phil has a water use licence to pump water from the Moeras, as well as access to an irrigation furrow, dating back to the late 1800s, which brings water to the farm from the Outeniquas. The quality of the mountain water is far better than the surface water on the farm, he says.

Major Challenges

According to Phil, the greatest challenge for most commercial dairy farmers is the cost-price squeeze.

“The cost of production [is increasing] faster than the price we are paid for our milk at the farm gate,” he says.

He therefore has to strive constantly for greater efficiency to ensure good margins. “A hotter, drier climate is a challenge for [many] dairy farmers, but biological farming and improving moisture retention in the soil by improving organic [content] is a way of addressing this.”

Value-added products

Being one of the smaller farms in the area, Milkwood does not have the benefit of extensive economies of scale, and this is further hampered by a limited water supply.

There is thus little scope to expand. However, in August last year, Milkwood Dairy started developing a small range of value-added dairy products – plain yoghurt, Greek yoghurt, kefir and labneh – in partnership with friends Tarryn and Garry Hampson.

“Tarryn processes these products from milk she buys from us, and they’re sold in select delis and health shops along the Garden Route, as well as restaurants,” explains Phil.

“It’s a way of building a sustainable business for the future and to pass on the opportunity to the next generation. So we’re growing vertically and will see where this venture takes us [by allowing it to] grow naturally. So far, market feedback has been very positive, so we’re encouraged.”

Breeding traits

Milkwood’s Holstein stud, Usherwood, is named after the original dairy farm near Kokstad. Artificial insemination is used exclusively; no bulls are used on the farm.

For breeding, Phil looks for “a cow that can produce economically on pasture”.

“She has to be able to walk well, so a cow with strength, functional traits such as longevity, fertility, [good] somatic cell scores, a medium frame and good milk [is preferable].”

He adds that selection criteria include the ability to produce good offspring that “will work on our farm and in our conditions”.

Milkwood sells surplus heifers to other commercial dairy farms in South Africa, as well as cross-border in Zambia. Bull calves are sold mostly to Karoo farmers who raise them for beef production.

Disease control

No female animals have been brought into the herd since the original 17 in 1957. This has reduced the risk of introducing diseases to the herd.’

“There’s always the chance of bringing in disease from other farms. It’s not foolproof, but it does help,” says Phil.

Cows in milk receive a monthly visit from the herd’s vet and testing for bovine tuberculosis and brucellosis is kept up to date.

“We have a comprehensive vaccination programme for brucellosis, bovine viral diarrhoea, Asiatic redwater, African redwater, gall sickness, lumpy skin disease, pink eye, three-day stiff sickness, and Rift Valley fever, when vaccine for [the latter] is available. We also vaccinate [gestating] animals with Rotavec Corona to [safeguard] newborn calves against gastro-intestinal problems.”

Mastitis control remains an important part of the dairy’s operation, but with the Afimilk system, individual cows can be identified and treated for mastitis.

Milk production

At Milkwood, calves stay with cows for four days. Cows are kept on pasture day and night, except when they are being milked twice daily and receiving their specially formulated dairy meal. In winter, cows graze by day, while at night they receive silage in troughs, but they remain outdoors all year round.

In winter, cows graze by day, while at night they receive silage in troughs, but they remain outdoors all year round.

Production averages about 5 000ℓ/day throughout the year. The lowest production months are February to May. Due to the farm’s long, narrow shape, the animals have to walk considerable distances, which affects production, he says.

“We’ve had cows peak at 42ℓ/day, although this is the exception on our pasture system. Our annual average is about 19ℓ/cow/ day,” says Phil.

Butterfat content is about 3,8%, protein content averages 3,35%, and the somatic cell count ranges between 200 000 and 300 000 year-round.

Success factors

“Doing away with all tillage and improving the organic levels of the soil is our greatest success, because everything starts in the soil. It’s still a work in progress, though.”

Phil stresses the importance of keeping an open mind and constantly learning.

“Beware of thinking you know everything, and be prepared to continue learning from other people.

“I’d like to improve our pasture and irrigation management.

We’d also like to grow the [dairy product] venture. I think dairy farming and supplying niche markets has a bright future and

I’m convinced we’re following the right system, being pasture-based. It’s sustainable and cost-effective and I think people are becoming more aware of eating healthy food. Dairy is one of these, so I’m optimistic.

“I also believe it’s critical to farm with conservation in mind, because we’re just the custodians of the land. This lifestyle is very fulfilling for me. It feeds my passion for the outdoors, soil conservation and healthy food production.”

Related news

Breeding Brahman cattle with superior genetics

Breeding Brahman cattle with superior genetics Heinrich Bruwer’s passion for superior Brahmans has led him to the best genetics in the world.

Beef cows: meeting their nutritional needs

Beef cows: meeting their nutritional needs Beef farmers should take care to match the nutritional needs of a cow to her production cycle to ensure optimal fertility rates, expecially when forage quality

Managing feed and breeding in replacement females

Managing feed and breeding in replacement females Heifers, first-calvers, maiden ewes and first-lambers need to be managed properly to reduce risk in terms of productivity versus production costs