How piglet weaning stresses impact gut health

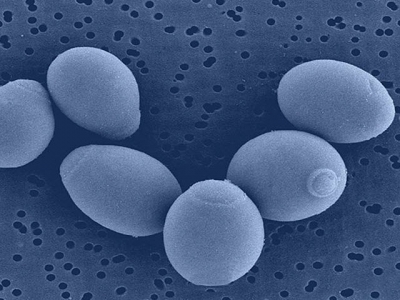

When S. cerevisiae boulardii yeast cells are used as a probiotic, the live yeast helps maintain and stabilize piglet microbiota. | Photo courtesy of Lallemand

Weaning is a source of major stress for the piglet, which has consequences on its digestive function including: reduction of feed intake, sub-optimal digestive process, gut morphology and digestive barrier function.

Weaning is one of the most stressful events in pig farming and can represent a true bottleneck in pig production. As the industry faces continued pressure to reduce antimicrobial use, the animals’ digestive microflora is gaining importance. Well-being, health and performance are closely related to the proper functioning of this invisible world.

Recent technological advances, such as metagenomics, helped gain deeper insight into the issues and stresses that surround weaning at the level of the digestive microflora — and how these could be addressed in the context of antibiotic reduction without sacrificing performance.

A stressful event

At weaning, piglets are faced with a combination of stresses to which they must quickly adapt, including diet, environment, social stress, maternal separation and more. Let’s focus on the impact of weaning stress on digestive physiology and function.

One of the first consequences of weaning is a drop in feed intake. Low feed intake leads to an erosion of digestive villi, causing a reduction of the gut absorption surface. This can impair nutrient assimilation and increase sensitivity to digestive pathologies.

The newborn piglet is enzymatically equipped to digest milk, but is poorly adapted to digest plant starch and proteins. For example, amylase and pepsin are not expressed at birth, and their expression is still far from optimal at six weeks. As a result, protein digestion is impaired at weaning. Feed conversion is less effective, and digestive disorders can arise.

While the piglet moves away from maternal milk, its own immune system is still fairly immature. Immune protection is sub-optimal, and the piglets will be more sensitive to sanitary challenges.

We are now aware of the tight relationship between the brain and the gut, and it is commonly accepted that stress has a negative impact on digestive function. Weaning is a source of stress, translated by physiological reactions such as the release of cortisol. Cortisol leads to the production of proinflammatory cytokines, some of which are linked to opening of tight junctions in the intestinal wall, which increases gut permeability and disrupts the digestive barrier function.

The piglet, its gut and its microbiome are intimately linked.

The intense stress of weaning can now be visualized at the level of gene expression in the gut. A recent study indicated the expression of more than 1,000 intestinal genes was affected by weaning, particularly genes involving the inflammatory response, defense against pathogens and the degradation of host tissues.

Consequences on the microbiome

The piglet, its gut and its microbiome are intimately linked. Weaning strongly impacts the piglet gut microbiota profile. Frese, 2015, attributes the changes during weaning to the sudden diet transition: from a milk-oriented microbiome (both enzymatically and metabolically oriented to the consumption of milk glycans, e.g., lactobacilli), to an increased population of saccharolytic microbes and an increase in populations expressing fiber degrading bacteria.

Weaning has a major impact on piglet microflora profiles.

After a potential fasting period, when piglets start eating again, the dramatic increase in intake can overcome the gut reduced capability. Partially digested feed can enter the colon, where undesired fermentations can occur, leading to an overproduction of short chain fatty acids. This helps explain the frequently observed incidence of post-weaning diarrhea.

In addition, the disruption of the gut barrier can lead to the translocation of undesired bacteria from the gut lumen, which can lead to further health issues.

Practices that affect the microbiota

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are a key tool for maintaining animal health in intensive farming. They are used to eliminate pathogens but represent one of the factors that impact the development of a healthy microbiota, and, sometimes, antibiotics can favor pathogen colonization. As an example, a current practice in human medicine, particularly in children, is to recommend probiotics to repopulate the gut at the same time as antibiotics are prescribed.

Zinc oxide

The general idea is to manipulate the intestinal microbiota in a positive way to promote lactobacilli and decrease the abundance of enterobacteria. However, some studies with high (pharmacological) doses of zinc oxide showed the opposite effect. In fact, reports suggest a link between the development of multi-resistant bacteria and high concentrations of zinc in the pig feed.

Fiber

Fiber can no longer be considered as an anti-nutritional factor in monogastric animals. According to Molist, et al., the use of certain amounts of insoluble non-starch polysaccharides (NSP) (wheat bran) together with soluble NSP (sugar beet pulp) had a positive effect on the microbial colonization and fermentation pattern in the hindgut.

The use of certain amounts of insoluble non-starch polysaccharides together with soluble NSP had a positive effect on the microbial colonization and fermentation pattern.

Probiotics

Modulation of gut microbiota by probiotics, such as the (live) yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae boulardii, has revealed distinct differences in bacterial community profiles between supplemented and control piglets. For example, piglets in the S. c. boulardii group showed a greater proportion of Lactobacilli population. In the same trial, antibiotic treatment profoundly affected the gut microbiota of weaned piglets, while administration of the probiotic maintained and stabilized the microbiota structure during antibiotic treatment. In this particular case, the difference in bacterial diversity and community structure between piglets supplemented with S. c. boulardii versus controls can be attributed to changes in the composition of low abundance taxa.

The supplementation of live yeast around weaning has a significant impact on microflora regulation on post-weaned piglets. PCoA = Principal Coordinates Analysis: each point represents a microbiota (specific time points and feed types); the closer together two data points appear, the more similar the bacterial communities.

Overcoming the negative consquences of weaning

The importance of a well-balanced, stable and healthy microbiota has been well-defined, as well as the risks associated with weaning or the use of antibiotics. It is evident that intestinal microbiota stabilization with a probiotic, like Saccharomyces cerevisiae boulardii, is a key tool in a management strategy aimed at overcoming some of the negative consequences of weaning, like diarrhea or the proliferation of pathogenic bugs in the context of antibiotic reduction.

Related news

Respiratory distress and ill-thrift in post-weaned pigs

Respiratory distress and ill-thrift in post-weaned pigs There is an increase of respiratory distress and loss of body condition with an increase of mortality in the weaning and growing pigs…

The effect of post-farrowing ketoprofen on sow feed intake, nursing behaviour and piglet

The effect of post-farrowing ketoprofen on sow feed intake, nursing behaviour and piglet The effect of post-farrowing ketoprofen on sow feed intake, nursing behaviour and piglet performance

Feeding rice bran to grow/finish pigs has benefits, trade-offs

Feeding rice bran to grow/finish pigs has benefits, trade-offs Rice is the third-most widely grown cereal grain worldwide, and the bran left over from milling white rice is available in large quantities for livestock feed